Violette Cordery (1900-1983, often shortened to Violet) was the daughter of Henry Cordery of Cobham, a tobacconist, and his second-wife, Berthe Petit. She had three sisters, an older half-sister called Leslie who married the noted car manufacturer Noel Macklin, and younger sisters Evelyn, who raced alongside Violette in the late-1920s, and Marise. She was described as a shy and unassuming girl with a matter-of-fact manner.

Violette took up driving when she was eighteen and in June 1920 she competed in the first Ladies’ race at the Brooklands racetrack and won. She drove a 10 horse-power Eric Campbell racing car and averaged 50mph. The following June she raced a Silver Hawk at Brooklands and came first; she went on to win another race a few months later. These achievements made her the first woman to hold any official records at Brooklands.

In January 1921 Violette made her first attempt at a time-trial record. Endurance driving was aimed at breaking records and fuelling the craze for progress and speed, as well as demonstrating the prowess of specific cars and manufacturers. Records were judged against a range of criteria, either the time taken to cover a specific distance (e.g the 200-mile record), the distance covered in a specific time (e.g. the four-hour record), or the average speed across a specific distance (e.g. 70 mph across 5,000 miles.)

For the 1921 attempt, Violette was part of the two-person team that broke several records for the 1,500cc class: the 200 mile record (3 hours and 10 minutes), the four hour record (covering just over 244 miles), and the 250-mile record (just over 4 hours and 5 minutes.) She was noted to be the first female driver to compete in such a record attempt. This is debatable, but she was certainly one of the earliest.

There are no further reports of her racing until May 1922 when she used her earlier experience of long-distance track driving to take part in a cross-country time-trial. Driving a B.S.A. 10 horse-power car she competed in a Scottish six-day trial over 1,040 miles of rough roads and steep hills, under particularly bad weather conditions. She was the only woman driver to not lose any marks and was awarded a gold medal.

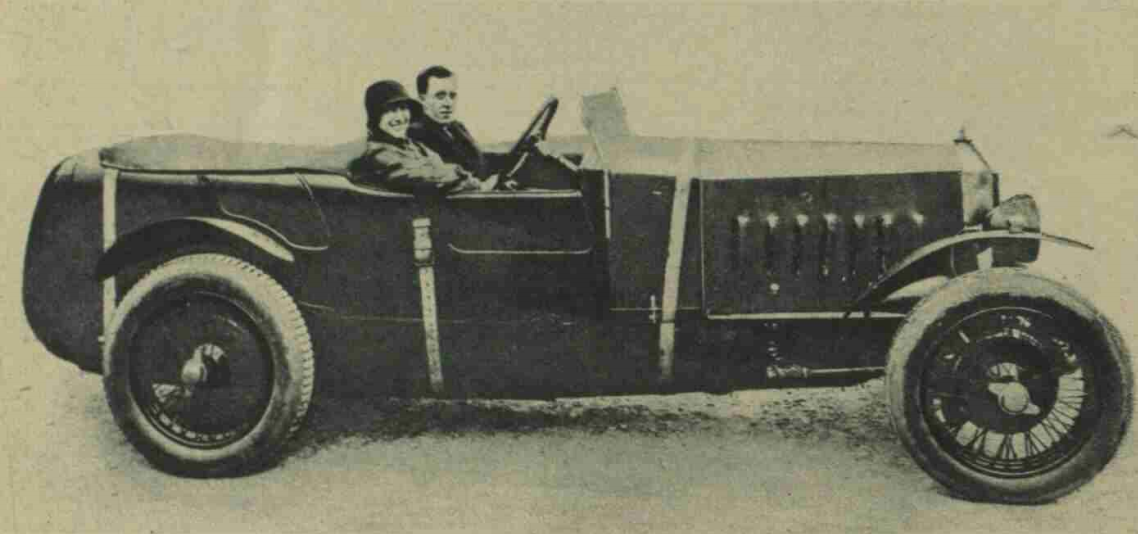

After another gap of several years, in July 1925 Violette won the half-mile sprint race at Brooklands against nine competitors, all of whom were men. She raced in the Invicta car which was been designed by Noel Macklin, her brother-in law. She would continue to race and compete in time and reliability trials in Invicta cars over the years. It seems likely that Macklin saw an opportunity to have a young woman publicise the car which was being promoted as a powerful but easy car to drive.

Violette’s first big motoring achievement came in March 1926 when she captained the long-distance team that broke thirty-three world records over 11 and a half days of non-stop driving on the world-famous Monza track just outside Milan. The records included the 10,000 mile, 15,000 km and 25,000 km. The latter was achieved by driving at an average speed of 89.7 kph. They drove a standard touring four-seater, six-cylinder Invicta.

During the attempt they also became the first team to drive 10,000 miles in 10,000 minutes. The team drove non-stop with 2.5 minute breaks every three hours; Violette was the only woman in the team and often drove for twice as long as her male teammates. Her demonstration of grit and tenacity captured the hearts of by the Italians who came to watch the first female racer on the world-famous track and the achievement was widely reported in Britain. On her return to London Violette was almost buried beneath a flurry of bouquets.

After a short-period of rest at home with her family in Cobham, Violette looked for her next big challenge. In the meantime she competed in a number of other races, including the one-mile challenge on the Southport sands which she won.

On 5 July 1926 she began an attempt to break the 5,000 mile record, choosing the Montlhery track in France for the attempt and driving a 19 horse-power Invicta car. Over the course of four days she smashed the record, driving at an average of 70.5 mph, and broke five other long-distance world records along the way. During the endeavour Violette made sure to promote the Invicta car, reminding the press that these feats were not being done in a racing car designed for track-driving, but in a standard British touring car intended for ordinary road-driving.

After achieving the new record, Violette announced that she had enjoyed the whole event apart from the hour and a half when a thunderstorm raged above the course: ‘I am terrified of lighting, more terrified of it than anything else in the world, and as I clung to the wheel and hurtled round the track at 80mph I was in a perfect funk.’

The significance of her achievements in the motoring world were recognised in October 1926 when Violette was awarded the Dewar Trophy by the Technical Committee of the RAC in response to her success in France. The Trophy was awarded to the most meritorious performance in a certified trial carried out under the club’s observation. Violette was the first woman to win the trophy and the fact that it was not awarded every year, but only on occasions when the RAC felt the accolade had been earned, gave it added prestige.

The significance of her achievements in the motoring world were recognised in October 1926 when Violette was awarded the Dewar Trophy by the Technical Committee of the RAC in response to her success in France. The Trophy was awarded to the most meritorious performance in a certified trial carried out under the club’s observation. Violette was the first woman to win the trophy and the fact that it was not awarded every year, but only on occasions when the RAC felt the accolade had been earned, gave it added prestige.

For the rest of that year Violette continued to race, taking part in less high-profile speed trials and short races at Brooklands, Southport and elsewhere. She won sixteen firsts, six seconds and one third. In a column for the Daily Express on 22 Oct 1926 she wrote: ‘there will soon be scarcely an able-bodied woman or girl who cannot drive and generally manage a motor car.’

Having already achieved so much in the record-books, Violette looked for a new type of motoring challenge and in January 1927, whilst recovering from a bad case of paratyphoid fever, she announced that she was resolved to be the first woman to drive a car around the world. She wanted to prove that women could be pioneers in long-distance travel, and also to demonstrate the reliability of British cars.

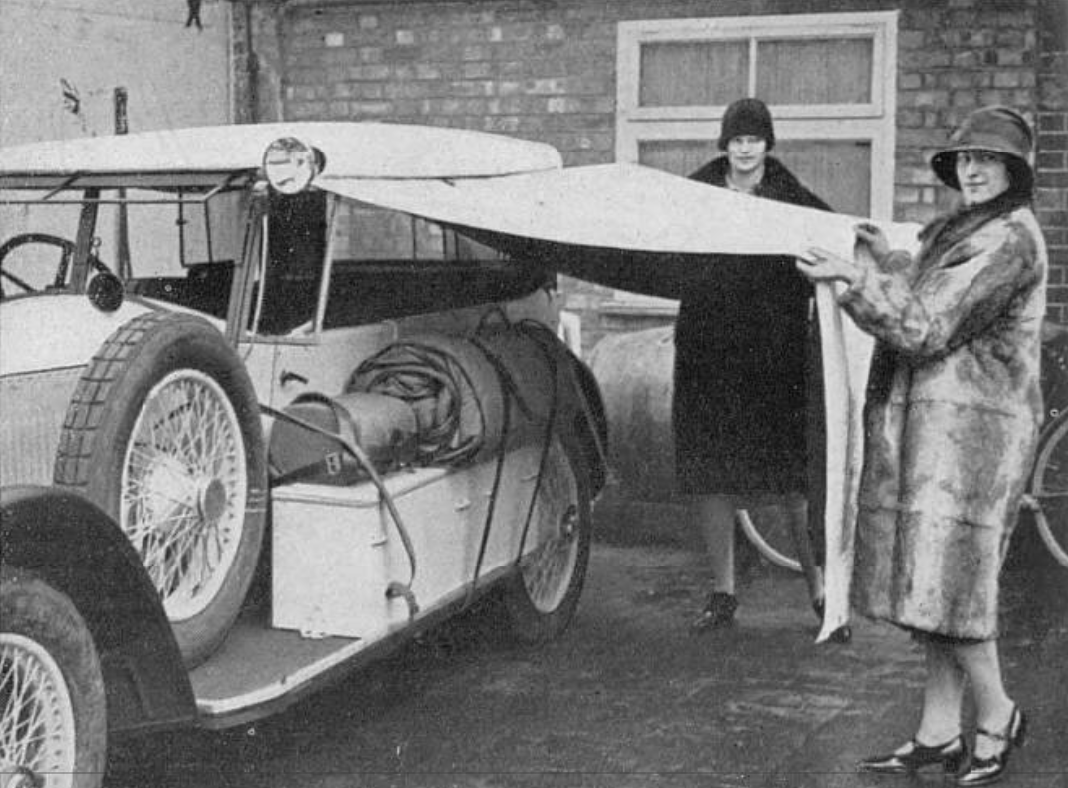

Violette was to be accompanied by her long-term mechanic, Ernest Hatcher, a close-friend, Eleanor Simpson, who was a trained nurse, and an RAC official to observe each stage of the trip. Just two days prior to departure, Violette had an arm in a sling as a result of her earlier illness but was determined to continue. Once again she drove an Invictus six-cylinder touring car, but it had a special robust chassis built for the trip. It was also adapted to allow the seats to fold down to create beds for the two women when a hotel was not an option and a tent attached to the side of the car for the two men to sleep under if required.

Each passenger was allowed no more than 20lbs of luggage and Violet was confident she would be able to fit ‘four sets of everything’ into her allocation. This included five evening dresses and four hats. The car carried a plaque of St Christopher, the patron saint of travellers, and they wore sprigs of white heather for good luck as they departed. As Violette and the team left her Cobham home she waved goodbye to her dog, Gin, and shouted to him that she was ‘just going for a ride.’

On 17 March they arrived in Bombay, by May they had crossed Australia and by the start of July the team had reached Quebec. In Melbourne Violette was given two mongooses which she carried in a cage across Australia with the aim of bringing them back to England.

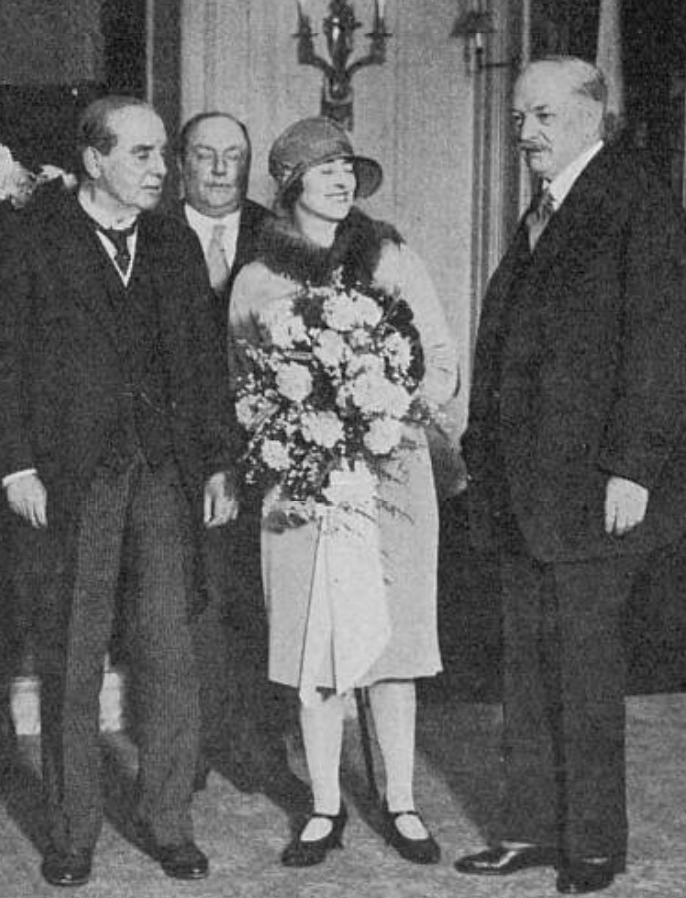

On 17 July the team arrived back at Southampton, Violette described the trip as ‘one long, glorious thrill.’ The following day they were given a grand reception at the Hyde Park Hotel where Lord Dewar, Sir Arthur Stanley (Chairman of the RAC) and Sir Charles Wakefield (whose company produced motorcar lubricant) praised her achievement. In a speech commending her achievement, Lord Dewar touched on the increase in women’s sporting achievements and joked: ‘The hand that rocks the cradle, will soon rock the ship of State.’ The Invicta car was put on display in Selfridge’s in the Artist’s Materials Department for the public to view.

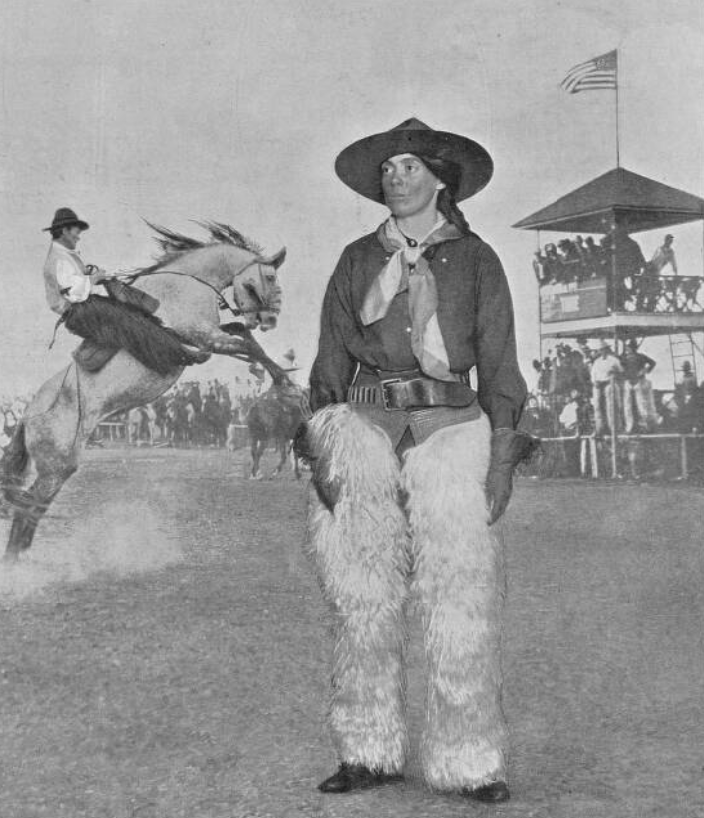

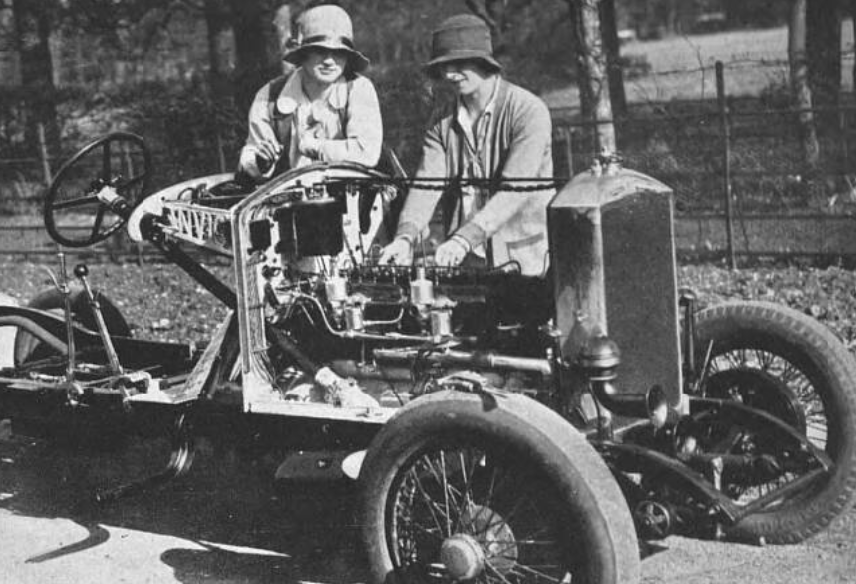

In the late 1920s Violette and her younger sisters, Evelyn and Marise, were living with their mother at The Cottage, Fairmile just outside Cobham in Surrey. By the summer of 1929 she was ready to take on another time-trial and set her sights on driving 30,000 miles in 30,000 minutes to establish a new world-record. Her younger sister Evelyn would assist with part of the driving; she was reported to be eighteen but was likely nineteen by the time the trial took place.

The endeavour took place over two months, starting in late June and finishing on 19th August. Each day of driving started at 8am and finished at 8pm; reports vary as to whether Evelyn did half of the driving or significantly less than that. It was said that their daily distance was the equivalent to driving from London to Scotland and they circled the Brooklands track over 10,000 times.

Violette once again drove an Invicta car, and the RAC officiated. Their record over 30,000 miles at an average of 61.57mph was still a world record in 1933. Footage from the event show Evelyn to be more confident and comfortable in front of the camera, Violette never appears to have been interested in the publicity other than for the recognition of her sporting achievements.

In October 1929 Violette was again awarded the Dewar trophy, this time for the Brooklands time-trial. She was the only person to have won the trophy twice in the history of the prestigious award.

Having also begun to show an interest in flying in the late 1920s, Violette had met John Stuart Hindmarsh whilst learning to fly. John was a fellow racing enthusiast, a pilot and a Lieutenant in the Royal Tank Corps. They married on 15th September 1931 in a quiet ceremony at Stoke d’Abernon church. Violette wore a simple gown in china-blue with the skirt tucked below the waist and full flares to the ankles. The outfit was paired with a matching felt hat and she carried sheaf of pink roses. They honeymooned in the South of France and in July 1932 had a daughter, Susan, who would later marry the racing driver Roy Salvadori. Their second daughter, Sally, was born in September 1935.

When she was engaged, Violette had told reporters she said she would ‘definitely’ give up racing when she married and her racing career does appear to have stopped, although she took part in the occasional rally. In 1933 she drove as part the winning team in an all-night Scottish rally.

Evelyn met her future husband, Lt. H.W. Newell of the Royal Queen’s Regiment, on a liner sailing to Kenya in May 1930. He was aide-de-camp to the Governor of Kenya and the couple married in December 1931 in Nairobi.

In June 1935 Violette’s husband, John, won the 24-hour endurance Grand Prix at Le Mans, the following year he was one of John Cobb’s team of four who went to Salt Lake City to attempt twenty of the world’s top motoring records. Tragically, on 7 September 1938 John was killed in a plane accident whist working as one of the chief test pilots at Hawker’s aircraft factory. It was reported his Hawker Hurricane hurtled down in a 400-mile-an-hour straight nose-dive, crashed in front of an empty house and exploded.

In June 1935 Violette’s husband, John, won the 24-hour endurance Grand Prix at Le Mans, the following year he was one of John Cobb’s team of four who went to Salt Lake City to attempt twenty of the world’s top motoring records. Tragically, on 7 September 1938 John was killed in a plane accident whist working as one of the chief test pilots at Hawker’s aircraft factory. It was reported his Hawker Hurricane hurtled down in a 400-mile-an-hour straight nose-dive, crashed in front of an empty house and exploded.

I was unable to discover anything further about Violette’s life after the the loss of her husband. She died at her home 13 Broom Hall, Oxshott, Surrey, on 30 December 1983.

Some images © Illustrated London News / Mary Evans