I’ve always been interested in explorers and travellers and the first half of the 20th century was ripe with men and women willing to set off into the unknown. Being an adventurer in this period required a confidence and brashness often associated with those from the upper-classes, and the money needed to finance expensive travels meant that many who took on such endeavours either had family money or were financed by wealthy men.

Although often presented by the press as ‘solo’ travellers, these adventurers usually had a number of guides, porters and others to assist them. But, in an age where long-distance communication was slow, or non-existent in some parts of the world, to travel even in a small group to areas uninhabited by Westerners came with dangers. For those used to a sheltered life in England, the possibility of danger and freedom from a restrictive society could be hugely enticing.

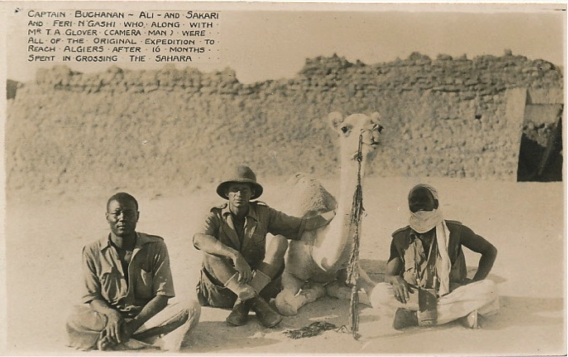

In the first of my series of unknown travellers and explorers, I’ve decided to focus on the Scotsman Angus Buchanan (1886-1954). I first came across him through the postcard shown above, where he sits in a relaxed manner on a camel. Long forgotten now, there’s not a huge amount known about Buchanan, but his 1922-23 trip across the Sahara was widely covered in the British press giving him a brief period of fame.

Born in Kirkwall on the Orkney Islands, off the very northern point of Scotland, Buchanan’s first travels was with a Zoological Expedition to the Barren Grounds in Australia in 1914, when he was 28. The following year, with World War One underway, he joined the 25th Royal Fusiliers and served for three years in East Africa until he was wounded whilst fighting in Beho-Beho and was sent home.

His first trip to the Sahara was in 1919 with a 1,400 mile expedition financed by the 2nd Baron Rothschild who was keen to find new species of animals in an unexplored area of Nigeria. This was a busy year for Buchanan, in June he married Olga Cherry in London and in July his first book, titled Three Years in East Africa was published.

On returning from his trip to the Sahara, Buchanan brought back over 140 mammals that Lord Rothschild gifted to the Natural History Museum. Eighteen of these were newly discovered species. The logistics of sending these back to England must have been impressive, and expensive!

Buchanan followed-up the trip with a book titled Exploration of Aïr: Out of the World North of Nigeria (1921), which was illustrated with photographs he had taken. In the book’s preface, he describes himself in the third person as ‘the traveller’ and suggests that he did not meet the contemporary expectations of an explorer:

‘It might be said that the traveller was a rude man, for he was untutored in the deep studies of the scholar of many languages, as in a measure might be expected and understood of one whose occupation called him from day to day to don rough clothing and shoulder a rifle and march outside the frontiers of civilisation.’

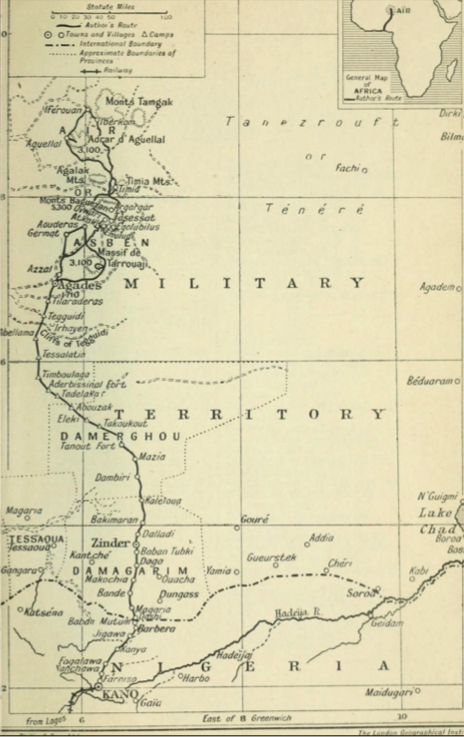

The beauty and mystery of the Sahara must have captured Buchanan’s heart, as in March 1922 he set out with the ambitious aim of crossing the Sahara from South to North. The adventure was very nearly halted when the French military authorities refused to allow the expedition to continue through the Aïr region of Nigeria and they were forced to turn back. Thankfully, on their way home they were overtaken by a messenger carrying news that they would be allowed onwards after all, so they headed north to complete the journey.

The group reached Algiers in June 1923, having collected a number of valuable scientific samples and data along the way to send home. The story was widely covered by the British and Colonial press who claimed that they were the first men to cross the Sahara by camel (I suspect that the implication here is that they were the first Western men to manage this achievement.)

This wonderful postcard print from 1923 brings us back to the reason I started looking into Buchanan – his camel! The image show Buchanan (centre) with two of the guides (Sakari and Ali) and Feri N’Gashi, the camel. Feri N’Gashi was one of the 32 camels (or 36, depending on different reports) used during the 11-month trip, and the only one to make it to the end in Algiers. Buchanan had already acquired a good knowledge of camels from his first trip to the Sahara so was likely well-equipped to pick a reliable camel. In his second book he wrote with fondness about the animals: ‘Select a good-natured beast from the rank and file, and hand-feed it with tit-bits of vegetation, and pet it when mounting and dismounting, and let no one else saddle it or ride it, and before long you will be astonished to find that you have won a queer pet and a useful obedient comrade.’ Sadly, accounts suggest that Feri died the day they arrived in Algeria.

To celebrate the arrival of Buchanan in Algeria, the widely read Illustrated London News published a double-page report on the expedition titled ‘Where man is veiled: the land of the Saharan Tuareg’. Here are some of the beautiful pictures taken by Buchanan:

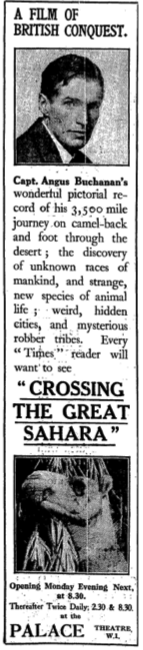

During the crossing of the Sahara, parts of the expedition were filmed by T.A. Glover who took the photograph of Buchanan with the guides and Feri N’Gashi. The film, shown in early 1924, was titled Crossing the Great Sahara and its introduction claimed it was ‘the First Photographic Record Ever Secured of the Life, Vastness and Mystery of the World’s Greatest Desert’. For the film’s opening night it was accompanied by music written by Herman Finck. The film does still exist in the BFI archives and reviews can give us some idea of the exciting experience it would have provided for viewers: ‘the film includes many pictures of the birds and beasts of these region, and there are also some glimpses of desert races, of the numerous robber bands who infest the country, and some of the cities in the cases which are said to have never been represented on the cinematograph before.’

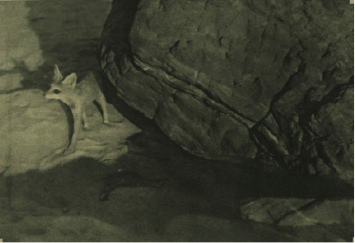

We can also get a glimpse of the film’s content from some photographs that were used in the film and that were also published in The Illustrated London News to coincide with the film’s release:

Whilst the film was showing at The Palace cinema in London it was accompanied by an exhibition of 500 species of animals and birds that Buchanan had brought back from the Sahara. For a brief period in 1924, Buchanan became a celebrity figure in Britain.

Whilst the film was showing at The Palace cinema in London it was accompanied by an exhibition of 500 species of animals and birds that Buchanan had brought back from the Sahara. For a brief period in 1924, Buchanan became a celebrity figure in Britain.

As a result of his travels, Buchanan wrote a number of books and proved to be a popular author amongst the public and critics. His style is authentic, but poetic and he often tries to compare aspects of these unknown lands to elements of life in England in an effort to help the reader relate to the exotic subjects.

This is clear in this excerpt from Out of the World North of Nigeria (1921) which detailed Buchanan’s 1919-20 travels to the Aïr region: ‘I cannot imagine a more barren country than Aïr in all the world: mountain after mountain of bare rock and far-reaching ground, bleak as a ploughed field in winter time, except for scant rifts of green along shallow sandy river-beds or close under mountain slopes. Without doubt Aïr is bleak almost as the beeriest desert…a vast, lifeless scene of rock and boulder and pebble.’

It is not clear what Buchanan did during the late 1920s and 1930s other than publish two novels: The City of the Seven Palms (1927) and Gain: A Tale of the Canadian Northland (1932). During World War Two he fought again, serving in Abyssina until he was injured in 1943. After this, I have unfortunately not been able to work out what he did until his death in 1954 in Edinburgh.

If anyone has any further information on Angus Buchanan or any better quality portraits of him I would be thrilled to hear about it.

Picture credits: Illustrated London News, The Times and National Portrait Gallery, London

I’m not sure if you’re still looking for information regarding Captain Angus Buchanan. If you are, I can help you some. Although I never met him, he was my father in law. I married his son, Angus, who was born in 1925 and passed in 2010. The last of the three children, Ann, died last year. The eldest, Sheila, died in 2008. I heard many stories about their home life.

My cool great-grandfather 🙂

Angus Buchanan was a distant cousin. Family legend is that he brought camels back to Scotland, where he used them to pull a carriage.

What a great legend! Although not sure how happy camels would be in the Scottish climate!

You might be interested to know that round 2011, I was able to watch (online) Crossing the Great Sahara at a UK public library: hopefully, despite the cuts hammering them, this service is still possible. I found it fascinating having worked in the region and having examined some of the local bird names he collected on both his trips to the Aïr mountains in Niger (not Nigeria as you mistakenly indicate).