Marjorie Elaine Foster (1893-1974) began shooting at the age of eight at her home in Surrey, England. In the mid-1920s she decided to pursue the sport more seriously and joined the South London Rifle Club, which was the only club that accepted women at that time. The first record of her competing is in 1926 where she performed well for someone new to the competitive world of rifle-shooting.

The pinnacle of her sporting career was in 1930 when she beat over 1,000 competitors to became the first woman ever to win the prestigious King’s Prize at the National Rifle Championships at Bisley. The competition, which began in 1860, was open to all past and present members of the Armed Forces. Marjorie was eligible to compete because she volunteered as a driver with the Women’s Legion.

She ended with a score of 280 out of a possible 300 points and won the competition with a bulls-eye fired at a 1,000 yards as her final shot. As winner of the prize, she had the distinction of being named Champion Shot of the Empire for the year. Pathé News have a wonderful bit of film of Marjorie being carried around Bisley on the chair as was tradition for the winner.

On hearing of her notable achievement the King wired his congratulations: ‘I most heartily congratulate Miss M.E. Foster on winning my prize, and that she should have done so is a wonderful achievement in the history of rifle-shooting, and as such will be universally acclaimed.’ As well as a message from the King, Marjorie had a deep-red rose named after her.

It would have taken some nerve to have competed in such a male-dominated sport, and there were certainly those who took offence at a woman taking part. As the King’s Prize was tied to those who has served or were serving in the Armed Forces, it riled some who felt that it did not show a suitable level of respect.

Marjorie’s skills meant she was sought after to play on national shooting teams and she represented England on many occasions at home and abroad. She continued to win competitions into her late fifties, winning a bronze medal at the Ontario Rifle Association’s annual shoot in 1952. The following year, aged sixty, she was vice-captain of the British team.

After retiring, she continued a strong association with the sport and served as the vice-president of the National Rifle Association. She was also secretary of the Commonwealth Rifle Club and coached promising members of the younger generations.

During the First World War, Marjorie had served as a driver with the Women’s Legion of Motor Drivers. She committed herself to service again in the Second World War when she was a senior commander in the Auxiliary Territorial Service (A.T.S.) and was badly wounded when commanding a transport company.

Alongside her career as a shots-woman, Marjorie ran a poultry farm at Frimley in Surrey. She lived there with her companion and fellow shots-woman, Blanche Badcock.

Even after her death in 1974 her allegiance to the sport continued; she left £1,000 to the National Rifle Association in her will. Her medals and trophies were left to the National Army Museum. At the time of her death Marjorie impressively still held the accolade of being the only woman ever to have won the King’s Prize.

I have enormous respect and admiration for Miss Forster. Her committed skills in shooting and her dedication to ‘Country’ via serving in two World Wars is to be commended at the highest level. An amazing lady

My aunt, Gladys Black (called Auntie Ginger ‘cos of her red hair) lived in Bisley Camp (shooting) in a house called The Barn, she was a great friend of Marjorie Foster who lived nearby. I met Miss. Foster on a number of occasions, a charming fascinating lady. She always wore grey flannel trousers, black blazer & beret. A cigarette in her hand. She had part of a finger missing. She & my aunt grew vegetables & used to compare notes.

What a great example Marjorie was to ladies wishing to engage in rifle shooting.

We very cheekily appointed Majorie a ‘past president’ of our club on the grounds that if she’d been alive, we would have asked her to fill this role.

Simon Rowe

The Nots SCA

She also shot a ‘possible’ 300/300 in a competition just before her kings prize win. No small feat with a .303 and the issued ammunition of the day.

Was Marjorie a member of the London and Middlesex Rifle Club at Bisley? I remember someone like her drinking pints and smoking cigars at the right hand end of the bar in the early 60’s.

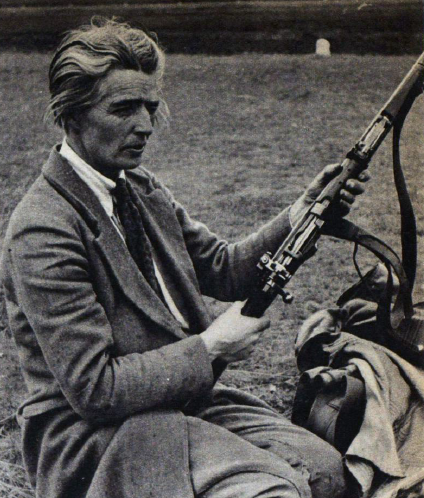

I used to take part in shooting practice and competitions… Initially pistol, as that was my preference, until this was banned. Later, rifle shooting, including visits to Bisley – What a charming place; enchantingly lodged in a previous era, and all the better for it. I have shot at 1000 yards, with a scoped modern rifle, albeit with military surplus ammunition… It is a very long way, even for a scoped rifle – Marjorie appears to be using a Lee-Enfield No4 rifle with some kind of target sights, but yet no magnification… Those who can appreciate her achievement are relatively few, but what an achievement !!