Lady Constance was a striking, flamboyant woman who was well-known in Britain and America for her career as a barefoot classical dancer, an unheard of profession for a titled woman. Her revealing dance costumes caused uproar and she espoused unconventional views on children’s education. Also applauded for her sporting prowess and adventurous travels, she was widely admired and held in high regard by those who knew her. As one newspaper commented, she was ‘a girl entirely out of the common.’

Constance was born in 1882 into Scottish aristocracy as the grand-daughter of the 3rd Duke of Sutherland. Her parents were Francis Mackenzie, 2nd Earl of Cromartie and Lillian (née Bosville-Macdonald), Countess of Cromartie. She had one older sister, Sibel, who also loved dancing. Their father died in 1893, leaving her mother and uncle as guardians to the sisters.

As there were no male heirs to the Earldom, the title went into abeyance, until 1895 when it was awarded to Sibel who became a Countess in her own right. This decision was followed by a court case disputing whether the inheritance that had been left by the Duke of Sutherland to the Earl of Cromartie (Constance’s father) with the aim of being passed onto his own heirs should be split between the two sisters or given solely to Sibel. The court decided in favour of Sibel. The case was appealed in the House of Lords in May 1896 and the Lords reversed the judgement, ruling that the sisters were to share their father’s estate.

In January 1896, aged fourteen, Constance left Scotland for a tour of the Continent with her sister and mother. In the summer of 1899, on return from several years at a Belgian finishing school, she entered ‘society’ and began attending key events in the Scottish and London social diary. In May 1900 she was presented at the royal court by her aunt, the Duchess of Sutherland. She wore an embroidered white tulle gown, trimmed with ribbon, with a train of mousseline satin which had a large chiffon bow in one corner and a spray of white roses. She carried a sheaf of white lilies tied with a pale green ribbon. Throughout the early 1900s she often attended society events with her aunt, the Duchess of Sutherland. In 1901 she travelled on the Duke’s yacht, ‘Catania’, to Paris and Venice.

Sporting Ladies

As well as attending the parties and charity events that came with her social position, Constance was an example of a new trend of high-born ladies showing great accomplishment at sports. She was a champion swimmer, a skilled rider, an expert shot, and a keen traveller. She could also play the bagpipes well, a nod to her family’s strong Scottish connection.

She was often described as a contrast to her smaller, more ‘delicate’ sister, with one description noting she was ‘tall and well built…[with] the grace born of exercise and perfect health.’ When in Scotland, she favoured wearing her own version of the traditional costume, consisting of a short kilt in checked tweed, green hose, buckled brogues, a green vest over a rose-pink shirt, the Mackenzie tartan, and a Glengarry bonnet with ribbons hanging over the shoulder. She caused controversy in the late 1900s when seen riding in London wearing ‘black leather leggings’ covered by a long black overcoat; at this point there was a growing fashion amongst society women to ride ‘astride’ instead of side-saddle.

In 1899, aged seventeen, Constance won her first swimming medal, when she won the Ladies’ Challenge Shield for excellence in swimming at the London Bath Club. Throughout the early 1900s she swam and taught at the Club where Princess Mary, daughter of the Prince of Wales (later King George V), and Iris and Felicity Tree, daughters of Herbert Beerbohm Tree, also learnt to swim. She went on to win the Ladies’ Challenge Shield the following two years. ‘Tatler’ magazine wrote that it would ‘be hard to find a prettier sight than when, dressed in her green swimming maillot and tartan waist ribbon, she passes along the line of swinging rings which are suspended above the water.’

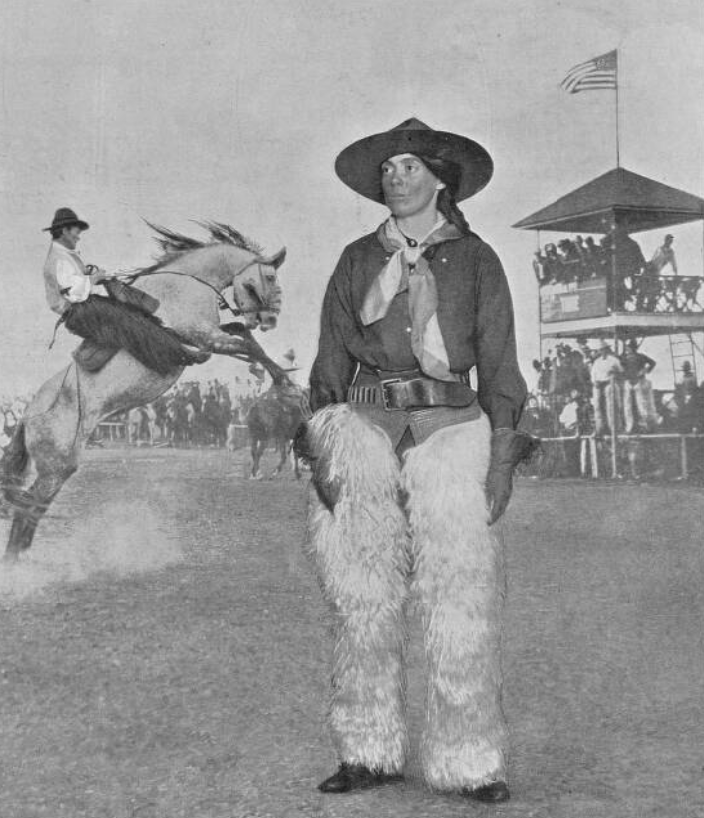

Constance the Cowboy

Throughout her life Constance made several trips to America. During her first trip in 1902 she hunted alligators, played golf in Chicago and stayed with Lord Minto, the Governor of Canada. Whilst in New York she reportedly walked ten to twelve miles each morning, through Central Park and Harlem, and would spend an hour fencing and boxing after breakfast and then take another walk before lunch. An American article announced: ‘She is English to the core, and has startled New York society. She rides astride, fences, dances, talks, sings, plays, and is an athlete. She attended a recital given by William C. Whitney in his New York home. Upon this occasion Lady Constance electrified the guests by performing a Highland sword dance….There seems to be nothing that this versatile young woman cannot do well.’ Towards the end of her trip, she was thrown from her horse in South Carolina and was knocked unconscious but recovered soon after.

The following year she returned to Texas for a hunting trip where she was accompanied by the famous hunter ‘Buffalo Bill.’ She caused a stir by riding in men’s overalls and it was claimed that she won the hearts of all the cowboys she came across. The portrait to the right shows Constance in a cowboy costume for the 1910 Chelsea Arts Club Ball, perhaps yearning to re-live her cowboy experience.

In the early 1900s Constance travelled alone and with friends to Egypt, Somaliland and India, causing a degree of scandal wherever she went. In Cairo the newspaper said she ‘caused a sensation by her appearance at a masked ball in the Gezireh Palace in bare feet and legs, from the knees down…Her costume…was as handsome as it was scant.’

Marriage to a young army officer

On 19 April 1904, aged twenty-three, she quietly married Sir Edward Austin Stewart-Richardson of Perthshire, a young army officer and a fellow Scot. The previous May, newspapers had reported her engagement to a Captain Fitzgerald, a young officer in the Royal Lancers, and as late as January 1904 the two were still attending society events together. But by April 1904 her attentions must have been drawn elsewhere, and a quick wedding to Edward took place instead. One paper suggested she had met Edward in Bombay on the way back from her 1903 travels to Somaliland. Edward had joined the army in 1890 and had went on to fight in the South African War and serve as ADC to the Governor of Queensland.

The wedding was a last-minute affair, with guests invited by telegram. Constance wore a biscuit-coloured cashmere gown, with a lace Victorian collar, large drooping sleeves, and a grey velvet belt which was repeated as the edging on the skirt. She accompanied the look with a large white felt hat with royal blue feather, and a white boa.

After the ceremony they travelled by carriage to the Cromartie family home, Tarbat House, in Ross-shire. Her popularity amongst locals was demonstrated by the crowds that lined the route and, as a gesture of thanks, the couple held a grand party for the the tenants on the estate and those from the nearby villages. Together the couple had two sons, Ian and Torquil. It seems to have been a happy marriage and Edward was not deterred by his wife’s eccentricities. When not travelling, they split their time between Pitfour Castle in Scotland and a house on Charles Street in Mayfair.

Scandal of the barefoot aristocrat

Up until 1909 there are few reports of Constance dancing other than referencing her skills at the traditional Highland dances. However, in 1908 there was much talk of her performance of a ‘Salome’ dance before the King at a private social event. At the end of the dance she sank to her knees and said, in the manner of the Salome,: ‘Sir, give me the head of Sir Ernest Cassel.’ Cassel was the King’s financial advisor, and although unpopular generally, was favoured by the King.

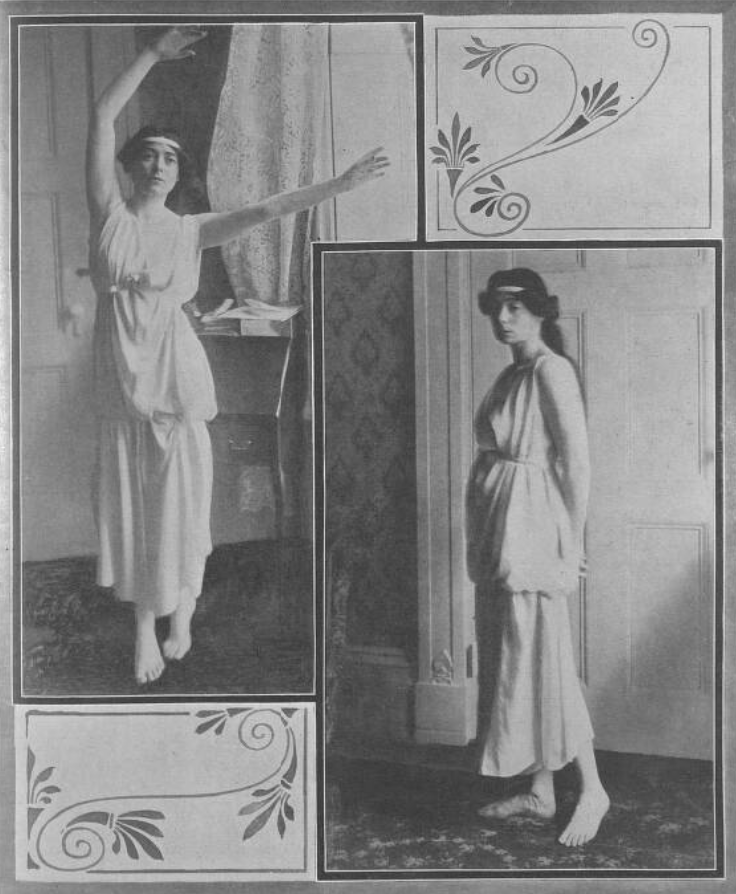

She seems to have occasionally danced at other private society events, but the first reports of her public ‘barefoot, classical’ dancing were in February 1909 when she danced at Sherry’s restaurant in New York. Presumably she felt it safer to make her foray into public performing outside Britain to begin with. It was certainly still considered fairly scandalous in America, so much so that Constance felt the need to ask the ‘Daily Mail’ to correct the ‘distorted notions of the character of her performance circulated by the American press.’ There was much interest in the event in the British press, with a mixture of shock and pride at the reaction Constance had caused in America. In March 1909 two photographs of her barefoot and in the ‘Grecian’ costume that she had worn in America featured on the front page of the society magazine ‘The Sketch’.

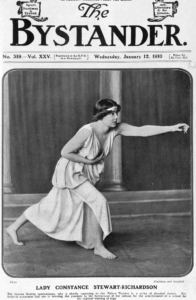

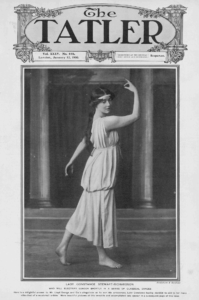

On returning to London, Constance offered to dance at a charity event being held at the Royal Opera House in London in aid of the Girls’ Realm Guild. She was perhaps seeking to capitalise on the publicity and attention she had received, or simply to stoke the controversy. Soon after the performance, it was announced that she had come to an arrangement with Alfred Butt, manager of the Palace music hall, to perform for to the paying public for one month in January 1910. She was reported to receive a salary of £1,000 a week, which she said would be used for charitable causes. She was to perform ‘a series of classical dances, and will introduce musical compositions for this purpose which have not hitherto been interpreted by dancing. In all her dances she will appear alone…and in all will wear a costume of a Greek style.’ She featured on the covers of two of the leading society magazines in the costume she was to wear.

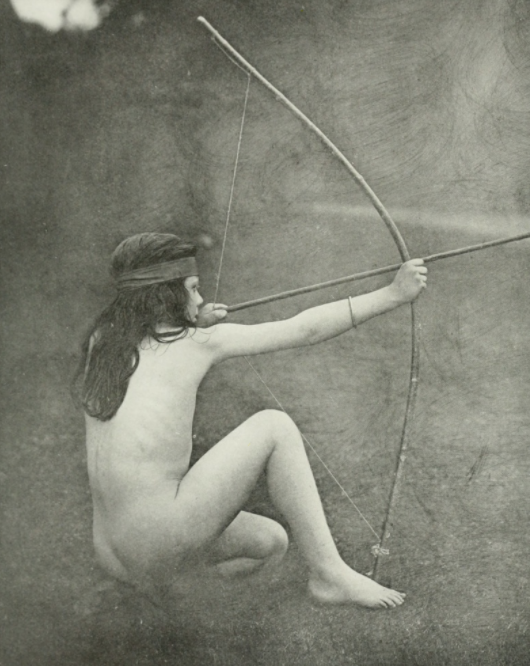

The run at the Palace Theatre, although controversial, was considered a success, and she featured heavily in the press at the time. Her dancing was compared to the daring dances by Maud Allan, Isadora Duncan and Gertrude Hoffman. She wore a flimsy, almost transparent costume which one reported said would be ‘tolerated if worn by a professional dancer’ but not by a woman of title.

‘The audience was silent until she had finished the last dance and then broke into thunderous applause.’ There were reports in American papers that, in reaction to her scandalous dancing at the Palace Theatre, the King had ordered that her name be struck from the court lists. There is no mention of this in any British papers so it is likely a fabricated story.

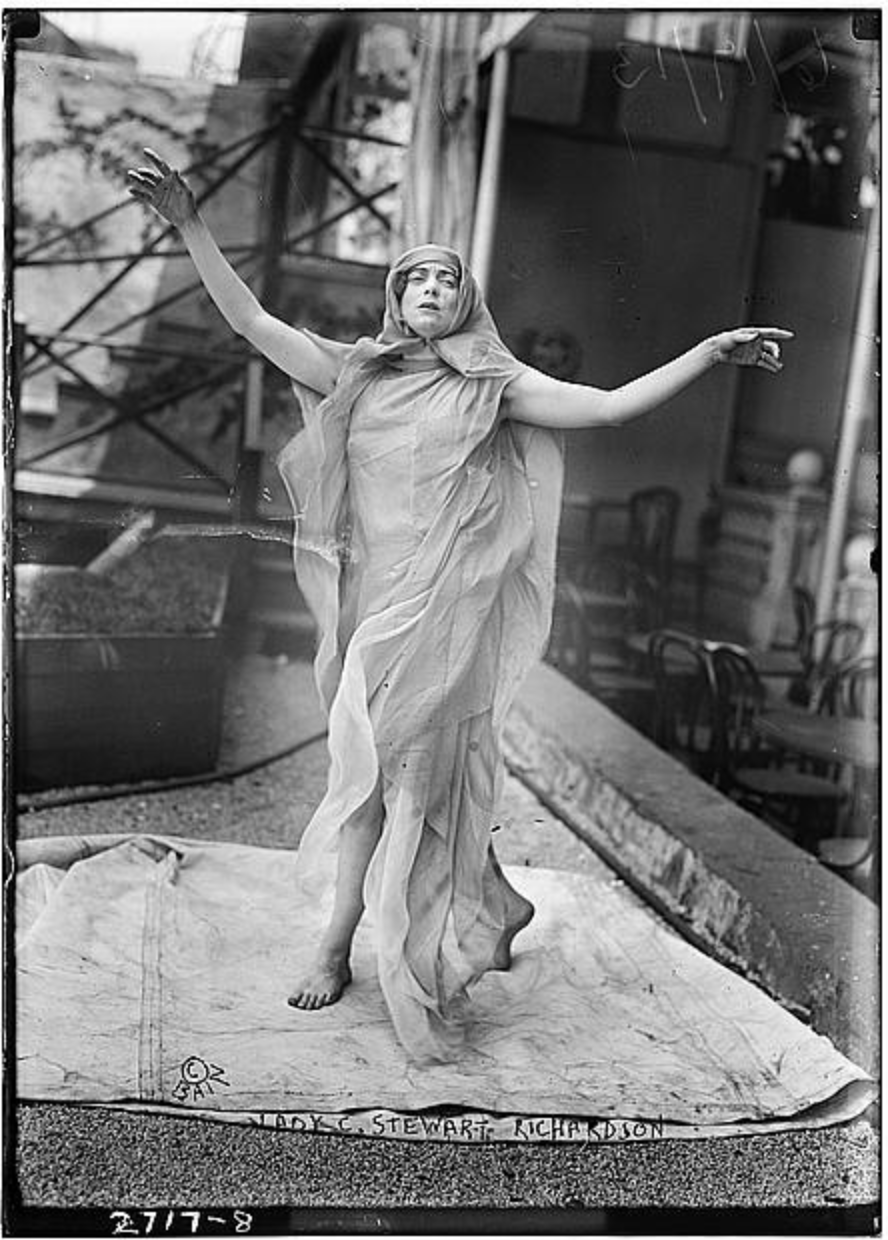

A few months later, in May 1910, she travelled to Paris to dance at the Alhambra for a month-long programme. In early 1913 she was dancing in Vienna in a drama called ‘Judith’ at the People’s Opera House where she ‘electrified Vienna.’ Off the back of these successes, Constance was invited to dance on a New York music-hall stage in June 1913, with a salary of around $1,000 a week. The engagement was at the Victoria music-hall on the corner of 42nd Street and Broadway, which was owned by Oscar Hammerstein, and the dancing took place on the roof-garden. She arrived in New York with her pet monkey, several snakes, and 40 pieces of luggage including a head-dress she had bought in Egypt. On the journey over onboard the ‘Olympic’ ocean-liner, she reportedly won a swimming contest against the actress Constance Collier who was also on board.

She followed the New York performances with a tour of America alongside Gertrude Hoffmann and Mme. Polaire. During the tour she collapsed on stage during a performance at the Court Square Theatre in Springfield, Massachusetts. The audience reportedly thought it was part of the show and applauded.

On her return she announced she was seeking simplicity, perhaps suffering from exhaustion from the whirlwind tour. To demonstrate this she set out from the Savoy Hotel, London, to tour the country by horse and caravan. But she soon returned to dancing and in October 1913 she set off on a world dancing tour. There is little noted about this tour so it may not have materialised. By early 1914 she was back dancing in America.

At the start of the Great War Constance’s husband Edward re-joined the 1st Battalion, Black Watch (Royal Highlanders). He was one of the early casualties of the war, dying on 28th November 1914 from wounds inflicted at the Battle of Ypres. Their son Ian inherited the baronetcy. Both sons would go on to serve in WWII: Ian gained the rank of Major and fought in Africa and Italy, and Torquil served as a Captain with the Royal Artillery Territorial Service and received the Military Cross.

Constance continued to perform throughout the duration of the war, throwing herself into performances in London and around the country. In 1915 she appeared at the Empire in London in The Wilderness, a Greek ballad-dance with words by Sturge Moore and music by Gustave Ferrari. She starred as a faun alongside Robert Roberty and the part of God Pan was played by Chief Kawbawgam who claimed to be descended from a ‘Red Indian tribe’. In one scene the two fauns fight at the top of a mountain and the first faun hurls the second down the mountainside.

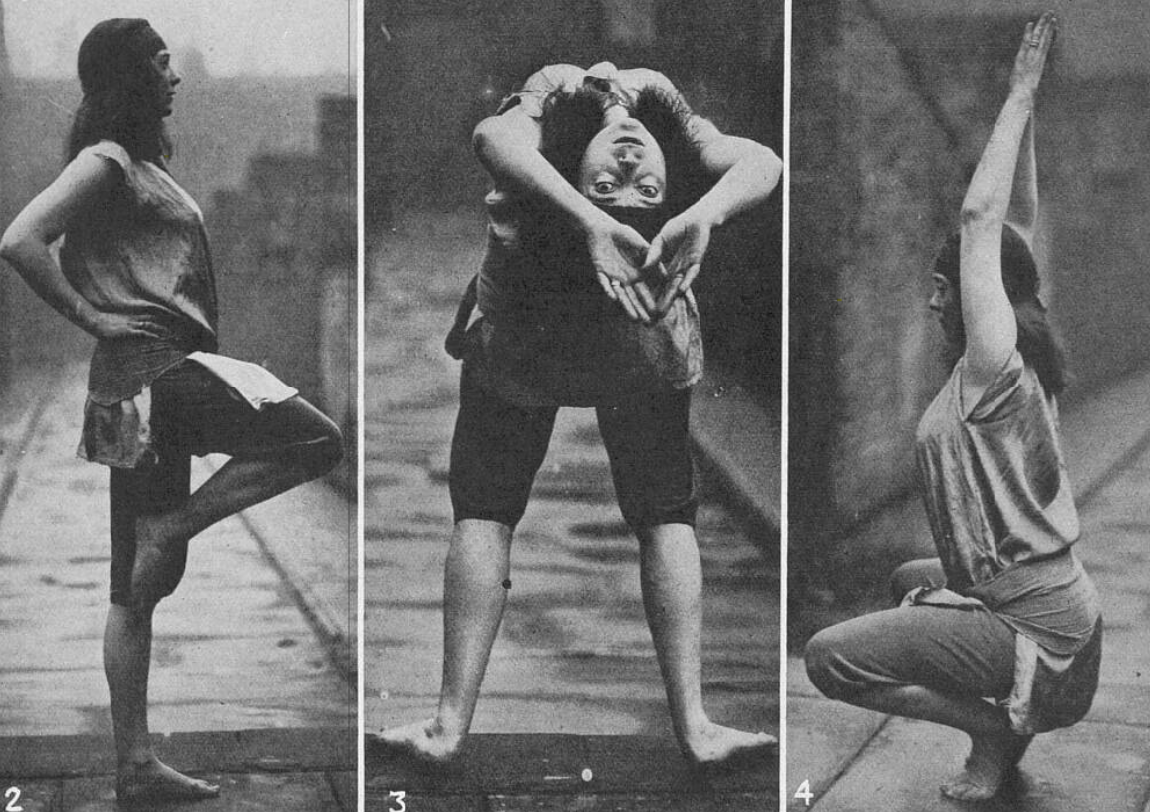

Constance’s only noticeable contribution to the war-effort was a series of exercises she proposed to improve the health of women working in factories:

The dancing muse

During this period a number of artists found inspiration in Constance. In 1914 the sculptor Prince Paul Troubetzkoy modelled a bronze sculpture on her and when describing Constance he observed: ‘it is rare that such exuberant vitality is combined with such perfect lines and grace of movement.’

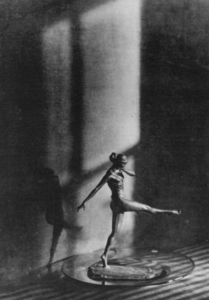

Two years later, in 1916, the noted photographer Arnold Genthe published a lavish book titled The Book of the Dance. Bound in rich blue buckram the book contained 93 full-page photographs and was intended to show ‘some of the phrases of modern dance tendencies that could be recorded in a pictorially interesting manner.’ It was a record of a moment in dance history. It featured three photographs of Constance dancing (I believe taken in 1913), as well as photographs of Maud Allan, Anna Pavlova, Lillian Emerson, and others. One reviewer said that Genthe had ‘done something close to the impossible. He has caught with splendid intuition, the sharply exotic and obviously dramatic quality of Ruth St. Denis; the slender and supple virtuosity of Anna Pavlova…the almost harsh vigor of Lady Constance Stewart Richardson…’

In 1917 Nina Hamnett painted Constance and she later recalled: ‘she was a most charming and interesting woman and my dreary existence was cheered up by her company… She had a marvellous figure and danced with not much more on than a tiger skin…neither of us had any money or, at least, very little and we ate often at a little restaurant in Soho where we got credit. I painted a portrait of Constance. She had a red turban on and a black robe, rather like a burnous that the Arabs wear. It was a good painting and bought by Sir Michael Sadler. I sent it to the National Portrait Society and it was accepted. On the day of the private view, Constance and I went. The place was full of all kinds of grand people. They all flocked to my portrait, expecting to see an almost nude woman. They were bitterly disappointed, and Constance and I laughed.’

The education of children

For Constance, one of the reasons for taking up professional dancing was in the hope of raising enough money to start a small school to educate a few young boys from infancy at their home in Scotland. She had a keen interest in methods of educating children, believing in the importance of the Greek ideal of a perfect harmony of body and mind.

Many of her theories were contained within her 1913 publication Dancing, Beauty and Games. She advocated that children should have as much exercise and freedom as they wanted: ‘for children the most natural [exercises] are the best – running, jumping, climbing, swimming, dancing and playing at ball –watched by a person who really understands the human body and who will correct little faults as they occur.’ She also felt that children should not be made to wear clothes. Reactions to her theories were generally negative; an American newspaper’s full-page article on the subject led with the headline: ‘With such a mother – what will finally become of Lady Constance Richardson’s unfortunate children – their father dead and their eccentric mother bringing them up in a strange, impossible way.’

Constance stuck by her teachings, and argued that she would not want her sons to become great professional figures but would prefer they had a simple future. Although some of her educational ideas were relatively forward-thinking she appeared to have an obsession with beauty, claiming: ‘I let [my children] look at picture books only after I have gone carefully through them and scissored every picture that shows the human figure other than perfect.’

In August 1921 Constance married Dennis Leckie Matthew, a wealthy bachelor. For the ceremony she wore a striking sand-coloured velvet gown ‘cut on Moorish lines’, with brown sandals and brown silk stockings. A sage-green burnous-cloak was draped over the gown and a peacock-blue silk scarf wrapped around her head like a turban, and wound under her chin.

I have been unable to find any details of Constance’s life after her second-marriage; it seems possible she moved abroad for some years. She died aged fifty in November 1932, it was reported that she’d been living in Italy shortly prior to returning to London.

Some images © Illustrated London News / Mary Evans

Thank you for a great article on this fascinating woman. May I ask where you sourced the Troubetzkoy quote ‘it is rare that such exuberant vitality is combined with such perfect lines and grace of movement.’? I am intrigued by his sculpture of Constance and am grateful for any advise on further information on where and when the sitting may have taken place, or if he in fact made it from a photograph.

Many thank you in advance,

Mary

Hi, I found the quote in an article in the ‘Los Angeles Herald’, 14 May 1914. They were close friends so I imagine she did sit for him. When Sotheby’s auctioned one of the casts they listed this as the source for their research so you may find something helpful there: V. Pica: ‘Artisti contemporanei: Paolo Troubetzkoy’, Emporium, xii, 1900, pp. 2–19; R. Giolli: Paolo Troubetzkoy, Milan, 1913); Sculture del principe Paolo Troubetzkoy, Milan, 1933; G. Piantoni & P. Venturoli, eds., Paolo Troubetzkoy exh. cat., Verbania, Paesaggio, 1990, no. 171, p. 211, M. L. Levkoff, Rodin in his Times, 1994, p. 188-93

This is a fascinating account of the early life of Constance much of which fills in gaps in my knowledge.

Dennis Matthews was my great-uncle and he died early in 1931. He had been in Valparaiso ostensibly managing nitre shipments to Europe but covertly working for the Foreign Office watching German movements at a time when war was looming…and he returned in 1914 to join the Leicester Yeomanry, apparently the tallest cavalry officer in WW1. My mother as a child remembered him carrying a revolver in the 1920s when he appeared to be a Kings Messenger. He and Constance had one daughter, Anita, who died in the early 2000’s and she had a daughter, Mary, who teaches dance in Hampshire. Mary has a drawing of Constance by Augustus John, probably proffered instead of payment for a restaurant bill!